On the heels of Cybersource Corp. v. Retail Decisions, Inc., an opinion that would have made Justice Douglas blush, the Federal Circuit has decided Classen Immunotherapies, Inc. v. Biogen-Idec et al., 2006-1634 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 31, 2011). What interested me most about this decision was Chief Judge Rader’s additional views in which he was joined by Judge Newman.

Chief Judge Rader took issue with patent attorneys responding to Supreme Court precedent by drafting claims to avoid abstract ideas. Chief Judge Rader characterized this as “gamesmanship.” This is disappointing because it reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what patent attorneys are doing. At a basic level, they are zealously representing their clients. At a claim drafting level, they are simply trying to color within the lines of what they believe to be the borders of eligible subject matter.

For example, if subject matter is a circle, and the outermost edge of the circle is a characterization of the subject matter that is so abstract as to constitute an abstract idea, drafting a claim to include that outermost area should violate section 101. However, if one doesn’t try to claim that outermost area, he or she should be fully entitled to claim the inner parts of the circle, whether that be an apparatus claim, a method claim, a composition of matter claim, or even an article of manufacture claim. For example, just because one can’t claim the idea of sitting, that doesn’t mean one shouldn’t be able to claim all types of chairs. The same holds true for Beauregard claims or any other type of claim that does not claim an abstract idea. The rules shouldn’t change just because software is involved.

The following is an excerpt of what Chief Judge Rader wrote in his additional views in Classen:

The patent eligibility doctrine has always had significant unintended implications because patent eligibility is a “coarse filter” that excludes entire areas of human inventiveness from the patent system on the basis of judge-created standards. For instance, eligibility restrictions usually engender a healthy dose of claim-drafting ingenuity. In almost every instance, patent claim drafters devise new claim forms and language that evade the subject matter exclusions. These evasions, however, add to the cost and complexity of the patent system and may cause technology research to shift to countries where protection is not so difficult or expensive.

The first unintended consequence, claim drafting evasion, has occurred several times in the past. After all, patents require a translation of technology into text, i.e., patent claims. Inevitably the subject matter exclusions of eligibility doctrines depend on the way that claims are drafted. Thus, careful claim drafting or new claim forms can often avoid eligibility restrictions. Eligibility then becomes a game where lawyers learn ingenious ways to recast technology in terms that satisfy eligibility concerns.

Two well-known examples of claim drafting to circumvent eligibility restrictions are the Beauregard claim and the Swiss claim. The Beauregard claim was devised to draft around restrictions on software imposed in Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63 (1972). Benson denied eligibility to mathematical algorithms, a category broad enough to endanger computer software in general. The Beauregard claim form, however, was for “computer programs embodied in a tangible medium.” In re Beauregard, 53 F.3d 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1995). Claims were re-drafted so that the intangible computer code in Benson instead became an encoded tangible medium in Beauregard. See id. at 1584 (PTO stating it will treat such claims as patent eligible subject matter); MPEP § 2106 (8th ed. Rev. 8, July 2010) (same).

…

When careful claim drafting or new claim formats avoid eligibility restrictions, the doctrine becomes very hollow. Excluding categories of subject matter from the patent system achieves no substantive improvement in the patent landscape. Yet, these language games impose high costs on patent prosecution and litigation. At the same time, the new games can cheat naïve inventors out of their inventions due to poor claim drafting. Moreover, our national innovation policy takes on characteristics of rewarding gamesmanship.

In addition to gamesmanship, eligibility restrictions increase the expense and difficulty in obtaining a patent. By creating obstacles to patent protection, the real-world impact is to frustrate innovation and drive research funding to more hospitable locations. To be direct, if one nation makes patent protection difficult, it will drive research to another, more accommodating, nation.

Classen, C.J. Rader’s additional views at pages 2-4 (emphasis added).

In response to Chief Judge Rader’s additional views, Judge Moore stood up for claim drafters noting that careful claim drafting is a virtue, not a vice. She wrote:

3 With all due respect to my colleagues, I do not agree with the additional views. First, the additional views improperly criticizes litigants for arguing that abstract ideas are exempt from patent protection. We are bound to follow Supreme Court precedent which clearly and explicitly holds that abstract ideas are not eligible for patent protection. Diamond, 450 U.S. at 185 (“Excluded from such patent protection are . . . abstract ideas.”); Parker, 437 U.S. at 589 (“[A]bstract intellectual concepts are not patentable . . . .”). Second, I favor “careful claim drafting” and think it a virtue, not a vice. If § 101 causes the drafting of careful, concrete, specific claims over abstract, conceptual claims, I see no harm. The world will have clear notice of the scope of such patent rights. Finally, in this global age, it is not immediately clear to me why the scope of patent rights should dictate the location of the innovation. Chinese companies do not move to the U.S. to carry out their research when they want a U.S. patent. Regardless, any decision on “national innovation policy” such as what will “frustrate innovation” or “drive research funding” should be left to Congress. We do not have the resources, institutional expertise or the mandate to weigh the competing incentives to innovation. Our job is to take the statute as we find it and apply it to the facts of the case before us.

Classen, Judge Moore’s dissent at pages 13-14 (emphasis added).

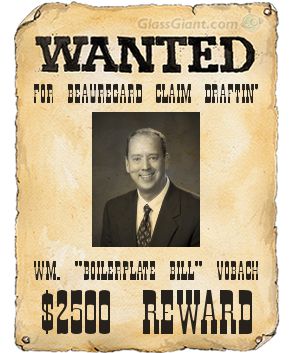

The recent demonizing of Beauregard claims and assertions of gamesmanship leaves one feeling a little bit like an outlaw in the old west:

* “Boilerplate Bill” is also wanted for continuation filin’, IDS submittin’, zealously representin’, gum chewin’, software protectin’, dog pettin’, Examiner collaboratin’, and algorithmin’. He is considered armed and dangerous, as his mild-mannered, patent attorney personality has been known to bore people to death.