UPDATED 9/25/2010

Spine Solutions, Inc., et al. v. Medtronic Sofamor Danek USA, Inc. et al., 2009-1538 (Fed. Cir. September 9, 2010) is an interesting case in that it deals with “adapted to” language and “operative engagement” language.

Claim 1 of the 6,936,071 patent, the only independent claim at issue, reads as follows:

An intervertebral implant insertable between ad-jacent vertebrae, comprising,

an upper part having an upper surface for engaging a vertebrae and a lower surface which includes a rounded portion,

a lower part having a lower surface for engaging a vertebrae and an upper surface portion in operative engagement with the rounded portion of the upper part,

said implant being constructed to be the sole im-plant in its intervertebral space,

the implant having a lead end which leads as the implant is inserted along a path into the intervertebral space and a trailing end opposite the lead end, and lateral planes which pass through the outermost boundaries of the implant and parallel to the said path, and

a single anchor on each of the upper surface of the upper part and the lower surface of the lower part, each said anchor being elongated, having a height greater than its width, and located along a line parallel to said path, the two anchors lying essentially in the same vertical plane, which plane is essentially midway between said lateral planes,

each said anchor being adapted to enter a groove in the adjacent vertebrae as the implant moves along said path into the intervertebral space, to anchor its respective part to the vertebrae which its surface engages.

The issue with respect to the “adapted to” language was whether the written description of the patent had been satisfied for the claim language “adapated to enter a groove.” This language was added after filing the application and according to the appellant had no basis in the specification. The court decided this isssue as follows:

Medtronic asserts that the district court erred in granting summary judgment that the ’071 patent contains adequate written description to support the limitation “single anchor . . . adapted to enter a groove.” We review a grant of summary judgment de novo, reapplying the standard applicable at the district court. Young v. Lu-menis, Inc., 492 F.3d 1336, 1345 (Fed. Cir. 2007). Sum-mary judgment is appropriate “if the pleadings, depositions, answers to interrogatories, and admissions on file, together with the affidavits, if any, show that there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and that the moving party is entitled to judgment as a matter of law.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 56(c). “Compliance with the written description requirement is a question of fact but is ame-nable to summary judgment in cases where no reasonable fact finder could return a verdict for the non-moving party.” PowerOasis, Inc. v. T-Mobile USA, Inc., 522 F.3d 1299, 1307 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

Claim 1 recites that the “single anchor” is “adapted to enter a groove in the adjacent vertebrae.” ’071 patent col.7 ll.3-10 (emphasis added). Medtronic argued that the written description does not disclose the “adapted to enter a groove” limitation. SSI argues that the ’071 patent necessarily discloses anchors that are “adapted to enter a groove” because it discloses that the adjacent vertebrae rest on the support faces of the intervertebral implant after insertion. The district court granted summary judgment holding that the claim was adequately sup-ported by the written description. We see no error in this judgment.

Medtronic is correct that the ’477 patent disclosure was not incorporated by reference and therefore cannot provide the disclosure of the “adapted to enter a groove” limitation. In the two pages Medtronic devotes to this issue, it argues that the patent makes no mention of grooves. See, e.g., Medtronic’s Br. at 37 (“patent’s failure to disclose any information concerning the grooves located in the vertebrae and their interaction with the anchor is a prime example of SSI’s attempt to expand its claims beyond its disclosures”); Medtronic’s Reply Br. at 8 (argu-ing that the patent diagrams do not show any grooves). Because the claims at issue relate to the implant and do not cover the groove itself, applicants were not required to disclose grooves or how grooves should be formed or cut. The limitation at issue does not recite cutting a groove into vertebrae, or even inserting an anchor into a groove; rather, it recites “a single anchor . . . adapted to enter a groove.” The issue for written description purposes is whether a person of skill in the art would understand the ’071 patent to describe a single anchor that is adapted to enter a groove. See Ariad Pharms., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336, 1351 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc) (“the test for sufficiency [of the written description requirement] is whether the disclosure of the application relied upon reasonably conveys to those skilled in the art that the inventor had possession of the claimed subject matter as of the filing date”).

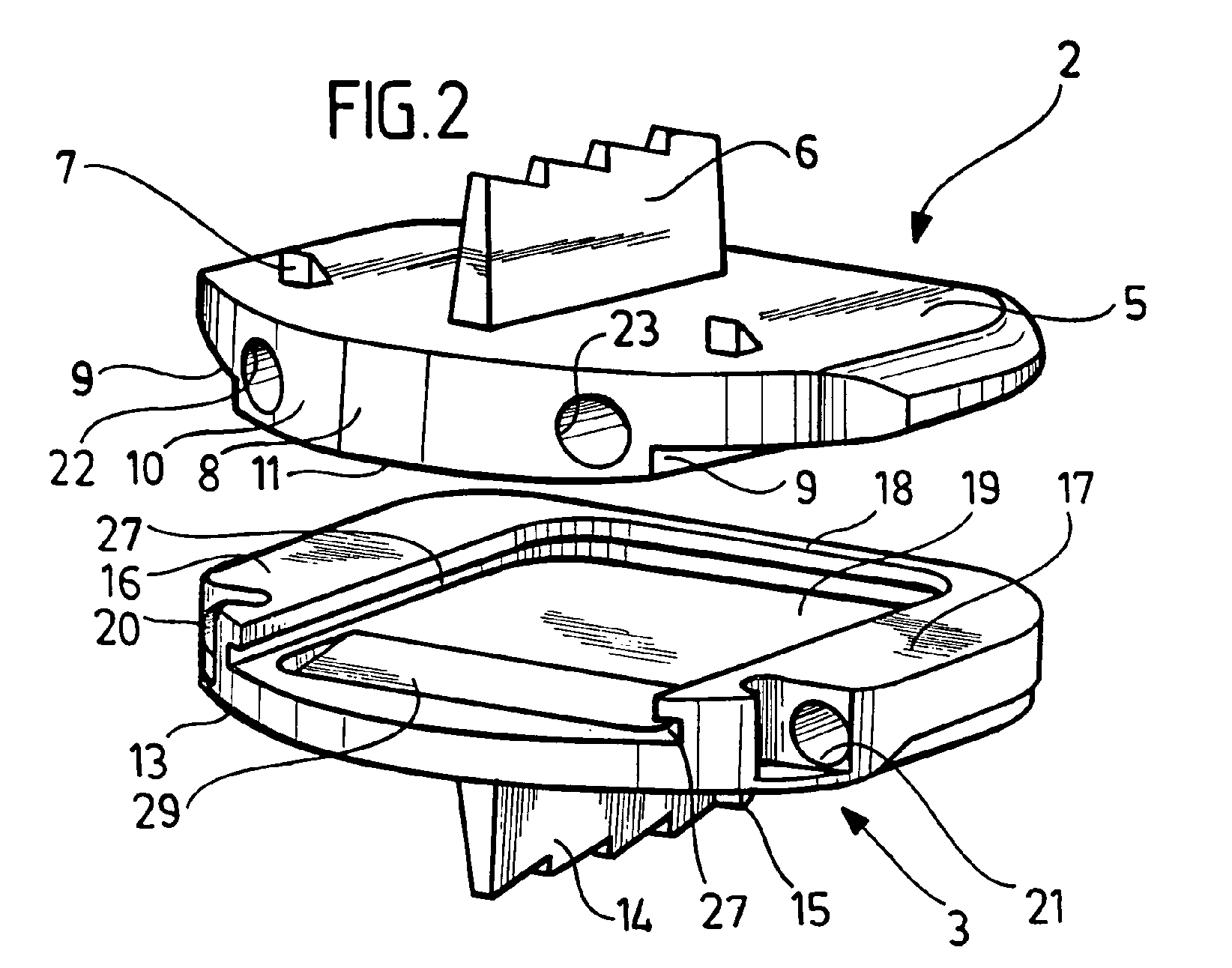

We see no error in the district court’s determination that there is no genuine dispute of material fact; the specification describes the claimed “single anchor” as necessarily being “adapted to enter a groove.” The disclosure of the shape of the anchor in combination with its placement adequately describes an anchor adapted to enter a groove. The specification discloses that each of the top and bottom parts of the implant has a support face that includes a single anchor. ’071 patent col.3 ll.56-58, col.4 ll.9-12, figs. 1-7. These anchors affix the upper and lower parts into the adjacent vertebrae such that the end face of each vertebrae “rests . . . on the support face” of the corresponding part of the implant. Id. col.3 ll.58-60, col.5 ll.59-64. Thus, the specification discloses that the single anchor enters the adjacent vertebrae in such a way that the vertebrae “rest” on the support faces of the top and bottom parts of the implant. For such direct contact between the implant and vertebrae to occur, the single anchor must be entirely inserted into the adjacent vertebrae: that is, the anchors must be fully inserted into a “groove” of some type, whether that groove is pre-cut or formed by the anchor itself (e.g., by a “self-cutting” an-chor). The specification, therefore, discloses that the single anchor is inserted into a vertebral groove. The record lacks adequate evidence to create a genuine dis-pute over whether the specification discloses that the anchors are “adapted to enter a groove.” The fact that the specification never mentions the word groove is not suffi-cient to create a genuine dispute of material fact.

We agree with the district court that the specification of the ’071 patent provides adequate written description to support the “single anchor . . . adapted to enter a groove” limitation. Therefore, we affirm the court’s grant of SSI’s motion for partial summary judgment dismissing Medtronic’s 35 U.S.C. § 112 defenses.

The parties spent a good portion of oral argument discussing the “adapted to enter a groove” issue. You can listen to Appellant’s argument [Here], Appellee’s argument [Here], and Appellant’s rebuttal argument [Here].

Another issue concerned the claim construction of the language “operative engagement.” The Appellant argued as follows: [Listen]. The Appellee did not have a chance to discuss this issue during oral argument.

The panel had the following to say in regard to “operative engagement”:

Medtronic asserts that the district court erred in con-struing the claim term “operative engagement.” Claim construction is a matter of law, and we review the court’s claim construction without deference. Cybor Corp. v. FAS Techs., Inc., 138 F.3d 1448, 1451 (Fed. Cir. 1998) (en banc). In doing so, we are mindful of the principle that “the claims of a patent define the invention to which the patentee is entitled the right to exclude.” Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1312 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc). We read the claims “in view of the specification,” which is “the single best guide to the meaning of a disputed term.” Id. at 1315.

Claim 1 recites the limitation of “a lower part having a lower surface for engaging a vertebrae and an upper surface portion in operative engagement with the rounded portion of the upper part.” ’071 patent col.6 ll.60-62 (emphasis added). At claim construction, Medtronic proposed construing “operative engagement” to mean “the interaction between the pivot insert and the rounded portion of the upper part.” Claim Construction Order, 2008 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 116648, at *18. The court ob-served that although the preferred embodiment of the ’071 patent has a pivot, claim 1 does not recite such a limitation: rather, claim 1 recites only an upper and a lower part that are “in operative engagement” with each other. The court also found that claim differentiation weighed against reading a pivot limitation into claim 1, because various dependent claims add limitations relating to a two-piece lower part with a pivot insert. Therefore, the court adopted SSI’s proposed construction, construing “operative engagement” as “permitting movement (for example pivotability).” Id. at *23.

Medtronic asserts that the court erred in construing “operative engagement” as not incorporating a pivot insert. According to Medtronic, the only “engagement” disclosed by the specification occurs between the upper part and the pivot insert, not between the upper and lower parts. SSI asserts that the court’s construction is correct because the plain language of the claim does not limit the invention to the preferred three-piece embodi-ment.

We agree with SSI that the court correctly construed “operative engagement.” The language of the limitation is straightforward: the lower part of the implant engages “operatively” with the rounded portion of the upper part. Given that the claimed invention is an intervertebral implant designed to replace a disc in a spinal column, “operative engagement” must be engagement such that the upper and lower parts of the implant can move rela-tive to each other; otherwise, the implant would be rigid and would inhibit movement of the adjacent vertebrae. Thus, the court correctly determined that “operative engagement” relates to permitting movement. The court also did not err in identifying pivotability as an example type of movement; the ’071 patent specifically discloses pivotability in association with the preferred embodiment. However, nothing in the claim suggests that the upper part of the implant must be specifically engaged with a pivot insert, as opposed to the lower part of the implant. To the contrary, the claim indicates that the upper and lower parts are engaged with each other directly. ’071 patent col.6 ll.60-62 (“a lower part having . . . an upper surface portion in operative engagement with the rounded portion of the upper part”). Therefore, the court did not err in construing “operative engagement” as “permitting movement (for example pivotability).”

Medtronic asserts, in the alternative, that under the court’s construction claim 1 is invalid for failure to comply with the written description requirement. Therefore, Medtronic argues, the court erred in granting summary judgment that the ’071 patent contains adequate written description to support the limitation “lower part having . . . an upper surface portion in operative engagement with the rounded portion of the upper part.” Medtronic argues that the ’071 patent only describes a three-piece device with a separate pivot insert, not a two-piece device that permits movement between the top and bottom parts. However, Figures 3 and 6 of the ’071 patent illustrate the implant outside the intervertebral space (i.e., prior to insertion) and show the pivot insert as embedded in the lower part. Additionally, the evidence at summary judg-ment included deposition testimony from Medtronic’s expert that a person of skill in the art would have known that an implant having a lower plate with an embeddable pivot insert—such as that disclosed by the ’071 patent—could have been assembled prior to insertion and inserted into the patient as a two-piece device. Medtronic does not point to any evidence rebutting this testimony. Therefore, we agree with the district court that a person of skill in the art would have understood the ’071 patent to describe an implant that could be pre-assembled prior to insertion, such that the upper surface of the lower part is “opera-tively engaged” with the lower surface of the upper part.

Medtronic contends that the ’071 patent does not de-scribe a two-piece implant because the ’071 patent ac-tively disparages the two-piece design of the ’477 patent. In discussing the two-piece design of the ’477 patent, the ’071 patent notes that it is “particularly difficult” to achieve a minimum structural height for an implant if the pivot is embedded prior to insertion. Id. col.1 ll.11-19. However, this does not rise to the level of an express disclaimer sufficient to limit the scope of the claims; “[d]isavowal requires expressions of manifest exclusion or restriction, representing a clear disavowal of claim scope.” Epistar Corp. v. ITC, 566 F.3d 1321, 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2009). Further, claim 1 is not directed to the height-minimizing embodiment. The originally-filed claims recited limitations directed to “protrusions and recesses . . . which are offset laterally from one another in such a way that . . . [the upper and lower parts] mesh with one an-other,” see J.A. 17167; claim 1 as issued recites no such limitation.

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Read].

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

You can review extrinsic evidence here: