The All Things Pros blog and IP Spotlight blog have noted that David Kappos issued a memo on January 26, 2010 in regard to the patent eligibility of computer readable medium claims (aka “Beauregard” claims): [Link][PDF].

Archive for January, 2010

Patent Eligibility of Computer Readable Medium Claims

Saturday, January 30th, 2010When should a “whereby clause” be treated as a claim limitation?

Thursday, January 28th, 2010The Federal Circuit quietly issued a Rule 36 opinion in Finisar v. DirecTV, 2009-1410 (Fed. Cir. Jan. 8, 2010) earlier this month. This was the second time that the Federal Circuit has addressed this dispute. In an earlier opinion, the court reversed the claim construction of a vital claim term, vacated a $78.9M jury verdict, and remanded the case back to the district court in the Eastern District of Texas. Upon remand, the district court subsequently found the remaining claims at issue invalid on summary judgment in view of the new claim construction.

An important issue on remand was the construction of a “whereby clause.” For example, claim 39 of the 5,404,505 patent reads:

39. An information transmission method comprising the steps of:

storing an information database on one or more memory devices;

generating and storing on said memory devices a set of indices for referencing data in said information database, including distinct indices for referencing distinct portions thereof, and embedding said indices in said information database;

scheduling transmission of selected portions of said information database, including assigning each selected portion of said information database a transmission repetition rate and one or more scheduled transmission times in accordance with said assigned repetition rate;

transmitting a stream of data packets containing said selected portions of said information database in accordance with said scheduled transmission times;

receiving said transmitted stream of data packets at subscriber stations;

at each subscriber station, storing filter data corresponding to a subset of said indices, said filter data specifying a set of requested data packets which comprises a subset of said transmitted data packets; and

at each subscriber station, downloading into a memory storage device those of said received data packets which match said specified set of requested data packets;

wherein said generating step generates indices including timestamps therein, said timestamps indicating when each said portion of the information database referenced by an index is to be transmitted;

said method including decoding said timestamps in said indices at said subscriber stations;

whereby subscribers can be informed as to when a specified portion of the information database will be received.

Surprisingly, with both Judges Rader and Moore on the panel, the panel passed up a golden opportunity to wade in on the issue of what test should be used when assessing whether a “whereby clause” is a claim limitation. Instead, the panel simply issued a Rule 36 opinion without any detailed discussion. Presumably, the panel felt that regardless of whether the whereby clause was considered a limitation, the prior art clearly invalidated the claims.

Nevertheless, the recording of the oral argument concerning the whereby clause issues is very interesting. Among other things, counsel for the plaintiff-appellant appeared to argue that the whereby clause was not simply an inherent result that necessarily followed from the preceding claim elements. Rather, purportedly the whereby clause addressed when data will be received. This distinguished the whereby clause as specifying when data “will be received” as opposed to when data “is being received” or when data “was received.” Thus, appellant’s counsel argued that the whereby clause actually added a further claim element that could not be inherent from the earlier claim elements, as it specified one of three possible options. [Listen]

Counsel for the appellee-defendant first countered that a “whereby clause” should be treated similar to a claim preamble and that claim preambles and whereby clauses are just bookends to a claim that state an intended result. Judge Moore then asked whether there should be a presumption that claim language that appears in the body of the claim should be considered a claim limitation. Appellee’s counsel then discussed the court’s two opinions on whereby clauses from the last decade Hoffer v. Microsoft, 405 F.3d 1326 (Fed. Cir. 2005) and Minton v. National Assn of Securities Dealers, Inc., 336 F.3d 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2003). [Listen]

Counsel for the appellant would later argue during rebuttal that the Hoffer case is in conflict with prior court precedent — which again begs the question of why this panel passed up an opportunity to wade in on the issue.

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

You can find the court’s opinion here: [Read]

*Like many oral arguments, this oral argument comprised a number of strong-minded individuals who spent a good deal of time talking on top of one another. If you’re like me in those situations, you may find yourself having flashbacks to the scene from “Cool Hand Luke” where the work camp warden says “What we’ve got here, is failure to communicate.”

I4I Files Response to Request for En Banc Rehearing

Wednesday, January 27th, 2010As you may recall, I4I v. Microsoft , 2009-1504 (Fed. Cir. Dec. 22, 2010) is the largest jury verdict of patent infringement to be affirmed on appeal. The Federal Circuit late last year affirmed the jury verdict of $200M in damages and $40M in enhanced damages as well as an injunction of the patented feature from Microsoft’s WORD software. [Link] Microsoft filed a Combined Petition for Rehearing and Rehearing En Banc. Yesterday, I4I filed its response to that petition.

You can read I4I’s response here: [Read].

See also:

Microsoft Requests Rehearing En Banc in I4I Case

Ariba v. Emptoris

Tuesday, January 26th, 2010The Federal Circuit recently affirmed the jury verdict of infringement in Ariba v. Emptoris, 2009-1230 (Fed. Cir. January 8, 2010). The patent at issue concerned an electronic auction. Interestingly, one of the claims at issue from US patent 6,216,114 was a Beauregard claim:

69. A machine-readable medium whose contents cause a computer to control overtime in an electronic auction, by performing:

a) defining a first time interval, a second time interval, a first overtime condition and a first closing time for a first lot, wherein said first overtime condition comprises:

receiving a plurality of bids;

assigning an ordinal rank to each bid from a best bid to a worst bid; and

receiving a bid having an ordinal rank that is within a predefined number of rank ordinal positions of best bid;

b) determining whether said first overtime condition occurs during said first time interval; and

c) extending said first closing time using said second time interval in accordance with said determination.

Again, the Federal Circuit affirmed the jury verdict of infringement of this Beauregard claim.

There was one question during the oral argument which struck me as odd. Judge Moore asked the attorney for the defendant-appellant whether the claim at issue was an originally filed claim. [Listen]. Perhaps it was just curiosity on Judge Moore’s part — I can’t think of any legal precedent that would require claims that were added or amended after a patent application was filed to be treated any differently during litigation for purposes of literal infringement than one would treat an originally filed claim.

The court’s rule 36 opinion is available here: [Read]. (Just a heads up that there is an error in the caption that has the attorneys who argued the appeal shown as representing the opposing party.)

Use of “present invention” in prosecution history

Sunday, January 24th, 2010While not mentioned in the court’s opinion, the Federal Circuit panel that heard oral argument in Catch Curve, Inc. v. Venali, Inc., 2009-1121, (January 22, 2010) inquired about a statement in the prosecution history that used the phrase “the present invention.” The court was trying to determine whether the term “fax protocol” of the patents should be construed to include packet switched network communications. A reference had been cited in the prosecution of one of the patents and that reference used packet switched network communications. The Applicant responded to the rejection by admitting that packet switched network communications would be encompassed by “the present invention” but that the cited reference could be distinguished on other grounds. Judge Bryson focuses on this issue in the following sound bite: [Listen].

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Read].

Hybrid Claims

Tuesday, January 19th, 2010The recently decided case of Schindler Elevator Corp. v. Otis Elevator Co., 2009-1146 (Fed. Cir. January 15, 2010) concerned a claim that read as follows:

1. An elevator installation having a plurality of elevators comprising:

a recognition device for recognizing elevator calls entered at an entry location by an information transmitter carried by an elevator user, initializing the entry location as a starting floor of a journey;a control device receiving the recognized elevator call and allocating an elevator to respond to the elevator call, through a predetermined allocating algorithm;

a call acknowledging device comprising one of a display device and an acoustic device to acknowledge recognition of the elevator call and to communicate a proposed destination floor to the elevator user;

the recognition device, mounted in the access area in the vicinity of the elevators and spatially located away from elevator doors, actuating the information transmitter and comprising a unit that independently reads data transmitted from the information transmitter carried by the elevator user and a storage device coupled between the unit and the control device;the recognition device one of transmitting proposed destination floor data, based upon the data transmitted from the information transmitter, to the control device, and, transmitting elevator user specific data, based upon individual features of the elevator user stored in the storage device, to the control device.

The Federal Circuit panel construed two claim limitations. Namely, it construed “information transmitter” to mean “a device that communicates with a recognition device via electromagnetic waves, after being actuated by that recognition device, without requiring any sort of personal action by the passenger.” And, the Federal Circuit construed the term “recognition device” to mean “a device that actuates and reads data transmitted by an information transmitter without requiring any sort of personal action by the passenger.” The strikeout shows the modification made to the District Court judge’s claim construction of the two terms.

Much of the oral argument concerned a discussion of what a user could or could not do. This was sometimes confusing because all the claims at issue were apparatus claims — not method claims. So, it seemed odd to be focusing on actions by the user. Nevertheless, the Federal Circuit states at one point in the opinion:

First, “the context in which a term is used in the asserted claim can be highly instructive.” Id. In claim 1, the term “information transmitter” itself suggests that the transmitter is a thing, separate and apart from an “elevator user” (a separate limitation), which transmits information. The claim also provides that “elevator calls [are] entered at an entry location by an information transmitter.” Thus, at least with regard to the transmission of information and the entry of calls, it is the information transmitter—not the elevator user—that performs these tasks. Similarly, the claim provides that a “recognition device . . . actuat[es] the information transmitter” and that “a unit . . . independently reads data transmitted from the information transmitter.” Accordingly, the tasks of actuating the transmitter and reading data are performed by the recognition device and the unit, respectively, not by the elevator user. The claim also explicitly provides that the transmitter is “carried by an elevator user.” Carrying a transmitter is thus a type of “personal action” that is expressly required in the claims. Nowhere does claim 1 limit the act of carrying to any specific manner of carrying.

(emphasis added)

Thus, the Federal Circuit noted that an elevator user is a separate claim limitation and that “carrying a transmitter” by a user is required by the claims. Moreover, the attorney for the plaintiff-appellant emphasized this step during oral argument: [Listen].

This would seem to suggest that at least claim 1 of Schindler’s patent is a hybrid claim that includes both structural elements and a method step that is performed by a user. How should this claim be treated under the Federal Circuit’s precedential opinion IPXL Holdings v. Amazon.com, 433 F.3d 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2005)?

In IPXL Holdings, the Federal Circuit held that a hybrid claim that included both structural elements and elements performed by a user of the system was indefinite under 35 USC section 112. The basis for the holding was that when a claim is written in this format it is unclear whether infringement occurs when one creates a system that allows a user to use the structure, or whether infringement occurs when the user actually uses the structure. The IPXL panel stated:

The district court found that claim 25 is indefinite under 35 U.S.C. § 112, as it attempts to claim both a system and a method for using that system. Section 112, paragraph 2, requires that the claims of a patent “particularly point[] out and distinctly claim[] the subject matter which the applicant regards as his invention.” 35 U.S.C. § 112 (2000). A claim is considered indefinite if it does not reasonably apprise those skilled in the art of its scope. Amgen, Inc. v. Chugai Pharm. Co., 927 F.2d 1200, 1217 (Fed. Cir. 1991).

Whether a single claim covering both an apparatus and a method of use of that apparatus is invalid is an issue of first impression in this court. The Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (“Board”) of the PTO, however, has made it clear that reciting both an apparatus and a method of using that apparatus renders a claim indefinite under section 112, paragraph 2. Ex parte Lyell, 17 USPQ2d 1548 (BPAI 1990). As the Board noted in Lyell, “the statutory class of invention is important in determining patentability and infringement.” Id. at 1550 (citing In re Kuehl, 475 F.2d 658, 665 (CCPA 1973); Rubber Co. v. Goodyear, 76 U.S. 788, 796 (1870)). The Board correctly surmised that, as a result of the combination of two separate statutory classes of invention, a manufacturer or seller of the claimed apparatus would not know from the claim whether it might also be liable for contributory infringement because a buyer or user of the apparatus later performs the claimed method of using the apparatus. Id. Thus, such a claim “is not sufficiently precise to provide competitors with an accurate determination of the ‘metes and bounds’ of protection involved” and is “ambiguous and properly rejected” under section 112, paragraph 2. Id. at 1550-51. This rule is well recognized and has been incorporated into the PTO’s Manual of Patent Examination Procedure. § 2173.05(p)(II) (1999) (“A single claim which claims both an apparatus and the method steps of using the apparatus is indefinite under 35 U.S.C. 112, second paragraph.”); see also Robert C. Faber, Landis on Mechanics of Patent Claim Drafting § 60A (2001) (“Never mix claim types to different classes of invention in a single claim.”).

Claim 25 recites both the system of claim 2 and a method for using that system. The claim reads:

The system of claim 2 [including an input means] wherein the predicted transaction information comprises both a transaction type and transaction parameters associated with that transaction type, and the user uses the input means to either change the predicted transaction information or accept the displayed transaction type and transaction parameters.

‘055 patent, col. 22, ll. 8-13 (emphasis added).Thus, it is unclear whether infringement of claim 25 occurs when one creates a system that allows the user to change the predicted transaction information or accept the displayed transaction, or whether infringement occurs when the user actually uses the input means to change transaction information or uses the input means to accept a displayed transaction. Because claim 25 recites both a system and the method for using that system, it does not apprise a person of ordinary skill in the art of its scope, and it is invalid under section 112, paragraph 2.

It will be interesting to see on remand to the District Court whether Otis Elevator pursues an indefiniteness argument under section 112.

You can read the Federal Circuit’s opinion here: [Read].

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

Book Review: “Drafting Patents for Litigation and Licensing”

Monday, January 18th, 2010

Reproduced by permission. ©2009 Colorado Bar Association,

38 The Colorado Lawyer 76 (December 2009). All rights reserved.

Book Reviews

Drafting Patents for Litigation and Licensing

By ABA Section of Intellectual Property Law, Bradley C. Wright, ed.

776 pp.; $325

BNA Books, 2008

P.O. Box 7814, Edison, NJ 08818-7814

(800) 960-1220l; www.bnabooks.com

Reviewed by William F. Vobach

William F. Vobach is a patent attorney and a partner with the intellectual property firm of Swanson and Bratschun in Littleton. He is co-editor of the Intellectual Property and Technology Law section of The Colorado Lawyer and a contributing author on “Patent Law” in the CBA’s The Practitioner’s Guide to Colorado Business Organizations—(303)268-0066, bvobach@sbiplaw.com.

Drafting Patents for Litigation and Licensing is an excellent book for anyone involved in the practice of writing patent applications, preparing patent non-infringement and invalidity opinions, or litigating patents. It will be less helpful to business attorneys who are not actively involved in counseling clients about patent law. However, for those attorneys who already have a general understanding of patent law and desire to learn more, this book will serve as a good reference.

Although patent attorneys are aware of the dichotomy between patent preparation and patent enforcement, not all attorneys might recognize a dichotomy exists. Although a patent application typically costs an inventor several thousands of dollars in attorney fees to prepare, millions of dollars typically will be spent when the patent is enforced. Thus, a significantly greater amount of money goes into enforcing an issued patent during litigation as compared to preparing the initial patent application. It therefore benefits all patent attorneys to be aware of the pitfalls that confront an attorney preparing a patent application. For example, it benefits not only those attorneys preparing patent applications so as to avoid these pitfalls, but also patent litigators looking for new arguments to attack an asserted patent.

This book focuses primarily on the preparation of patent applications and the pitfalls that can confront a patent attorney during the application process. In the first chapter, the current state of the law of claim construction is discussed. Then, a very useful chapter discusses the problems that can occur when drafting a patent application. The next chapter draws on the lessons learned from claim construction cases to propose a process that the attorney can employ when preparing a new patent application. I found these first three chapters of the book to be an excellent refresher on the recent developments and trends in patent law. Moreover, I have continued to refer back to them while I have prepared opinions or drafted patent applications.

The next third of the book deals with technical areas of patent law and the issues that are unique to each area. There are chapters focusing on mechanical patents; electrical patents; chemical and pharmaceutical patents; biotechnology patents; software, e-commerce, Internet, and business method patents; and design patents. The chapters are authored by specialists in their respective area of patent law and therefore are well tailored to address issues that confront practitioners in each technical specialty area. The chapter on design patents is one of the better treatments of this area of the law that I have seen.

The third section of the book discusses other topics of interest to patent attorneys, such as continuation practice, drafting patent applications with a view toward Europe, and combining patent prosecution with other forms of representation. The subject matter in these chapters, including the discussion about a firm serving as both opinion counsel and litigation counsel, is particularly well presented. Among the authors is David Hricik, who is one of the leading scholars on ethical issues confronting patent attorneys.

Due to the frequency with which changes occur in patent law, there have already been some significant changes in the law that will have to be updated when the book is supplemented. However, there is no avoiding this issue in books of this nature and I would not put off ordering the book until a supplement is released. Even without a supplement, the book will be valuable for many years to come.

I can highly recommend this book to all patent practitioners—both patent prosecutors and patent litigators alike. The authors selected to write each chapter clearly know their subjects and do an excellent job of presenting the material. The book is well crafted to assist those in the practice of drafting, litigating, or licensing patents to assist their clients in assessing the strengths and weaknesses of a patent.

Review of Legal Resources is published to apprise attorneys of books and other resources that may be of interest to them. Readers wishing to make review suggestions, provide review copies, or write reviews should contact Leona Martínez at leonamartinez@cobar.org. For a list of titles available for review at press time, see the notice on page 124 entitled “Read a book. Write a review.”

Readers who have questions about any reviewed material should contact the reviewer. Please contact the publisher to obtain a copy of the book.

CBA members can purchase any ABA publication at a 20 percent discount through the CBA’s Department of Law Practice Management (LPM). Some materials may be available for checkout through the LPM Lending Library. For more information about LPM purchases and the LPM Lending Library, contact Michelle Gersic at (303) 824-5342, (800) 332-6736, or mgersic@cobar.org.

The Colorado Lawyer | December 2009 | Vol. 38, No. 12

Water cooler talk

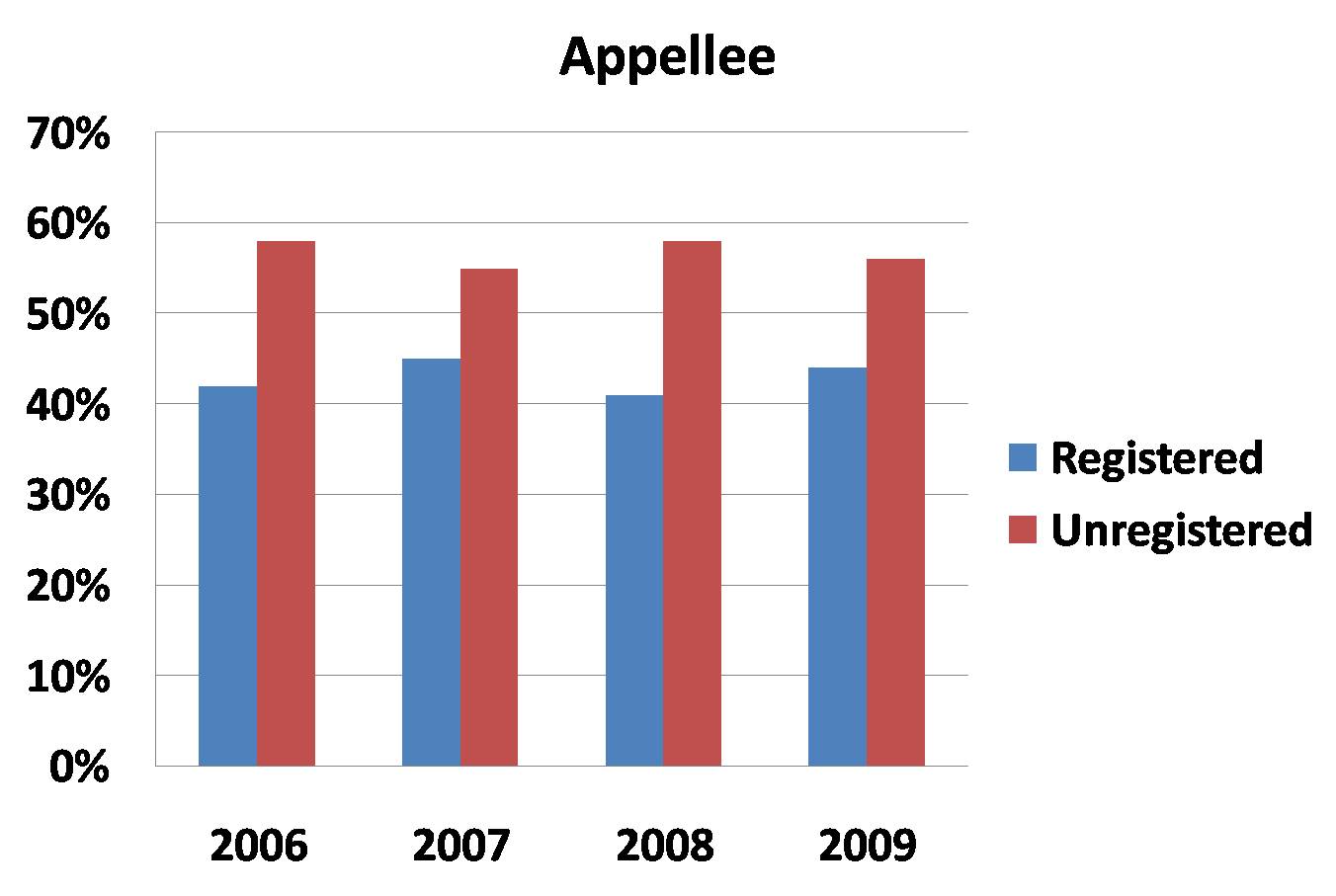

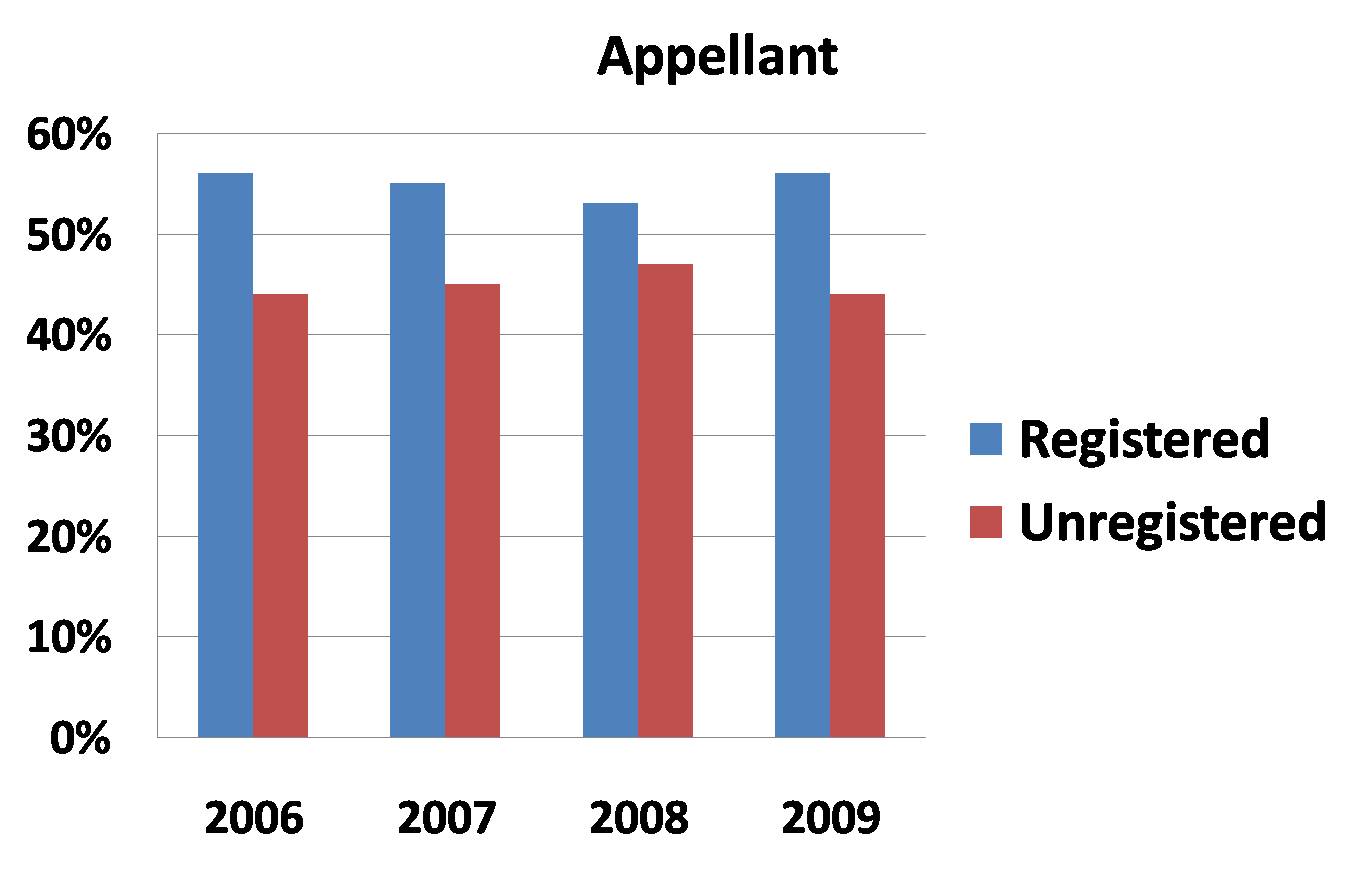

Monday, January 11th, 2010Are registered patent attorneys more successful litigators than those attorneys who are not registered? I imagine the answer you get to that question will depend on whom you ask. In looking at the number of registered attorneys arguing patent cases at the Federal Circuit, however, I found the breakdown between registered attorneys and unregistered attorneys extremely interesting. There is a clear pattern of there being a greater percentage of unregistered attorneys arguing on behalf of appellees. And, a clear pattern of there being a greater percentage of registered attorneys arguing on behalf of appellants.

So, as fodder for discussion around the water cooler, what do these statistics mean, if anything? Does the higher percentage of unregistered attorneys representing appellees mean that unregistered attorneys are better trial lawyers, can think more like jurors or judges, are highly skilled appellate lawyers at general practice firms? Does the higher percentage of registered attorneys representing appellants mean that when the stakes are high, parties bring in a hired-gun appellate lawyer with a registration number? What about the high reversal rates at the Federal Circuit — what do they suggest about the ultimate outcome of a case? Do the trends have anything to do with movement of patent litigation and patent litigators away from boutique patent firms to large general practice firms? I don’t know the answer to these questions — but, I do find the opposing trends interesting.

Microsoft Requests Rehearing En Banc in I4I case

Saturday, January 9th, 2010Microsoft has now filed its request for a rehearing en banc in the I4I v. Microsoft appeal: [Read].

What does “connect” mean?

Wednesday, January 6th, 2010If you have ever written mechanical patents or spent time analyzing them, you have probably run across the issue of how broadly should the word “connect” be interpreted. (Similarly, you have probably contemplated the meaning of “coupled with.”) The case of Restaurant Technologies, Inc. v. Jersey Shore Chicken, 2009-1176, (Fed. Cir. January 6, 2010) broached this issue with respect to the word “interconnecting.” The patent at issue concerned a chicken fryer.*

The claim term at issue read:

(e) piping network interconnecting said first and second containers, said filter unit and said first and second couplings.

One of the interesting aspects of the oral argument was when Peter Lancaster of Dorsey and Whitney’s Minneapolis office made the argument that the defendant’s own patent (stipulated to describe the accused device) described the elements of the allegedly infringing product as “connected.” [Listen]. In my review of the court’s opinion, I did not see that the panel ever addressed that argument.

The panel also noted that the doctrine of equivalents would not cover indirectly connected elements — elements are either connected or not connected.

Furthermore, the court was correct in limiting possible equivalents as a matter of law, finding that claim 8, paragraph (e), “warrant[s] few or no equivalents because there are no insubstantial or trivial changes that could be made to this limitation; the specified components are either connected or not connected to one another by a piping network.” Summary Judgment Opinion, 2007 WL 4081737 at *19. Based on the claim construction, the court was correct in finding that Oilmatic was entitled to summary judgment of noninfringement.

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Read].

*Appropriately, the inventors for the chicken fryer patent at issue hail from Kentucky.

Do you speak American?

Sunday, January 3rd, 2010PBS has an interesting website on American English at http://www.pbs.org/speak/ that they title “Do you speak American?” One fun page at the site is an interactive quiz to see if you can match a speaker to a region of the country: [Link].

Another page explains how various presidents have coined new words throughout the years, such as “administration,” “lunatic fringe,” and “misunderestimate”: [Link].

The article refers to one who coins new words as a neologist. My reaction to reading that was “Oh, they meant to say lexicographer.” But, it turns out that PBS has the better word. According to my dictionary, a lexicographer is “a writer, editor, or compiler of a dictionary.” However, neologize means “to make or use new words or create new meanings for existing words.” It would seem that a lexicographer is merely a person who records established definitions rather than the more creative neologist who coins entirely original meanings for words.

A lesser known corollary to the lexicographer [sic: neologist] rule is that a patentee is also entitled to be his or her own grammarian. See Chicago Steel Foundry Co. v. Burnside Steel Foundry Co., 132 F.2d 812, 814-15 (7th Cir. 1943), cited in Jonsson v. Stanley Works, 903 F.2d 812, 820-21 (Fed. Cir. 1990).

*By the way, while playing SCRABBLE over the holidays, I tried to explain to my family that as a patent attorney, I was entitled to be my own lexicographer [sic: neologist] when proposing new words on the board. They didn’t buy it.