The amicus briefs in support of Arthrex were filed recently. You can review them here:

I thought these statistics from TiVo’s brief were interesting:

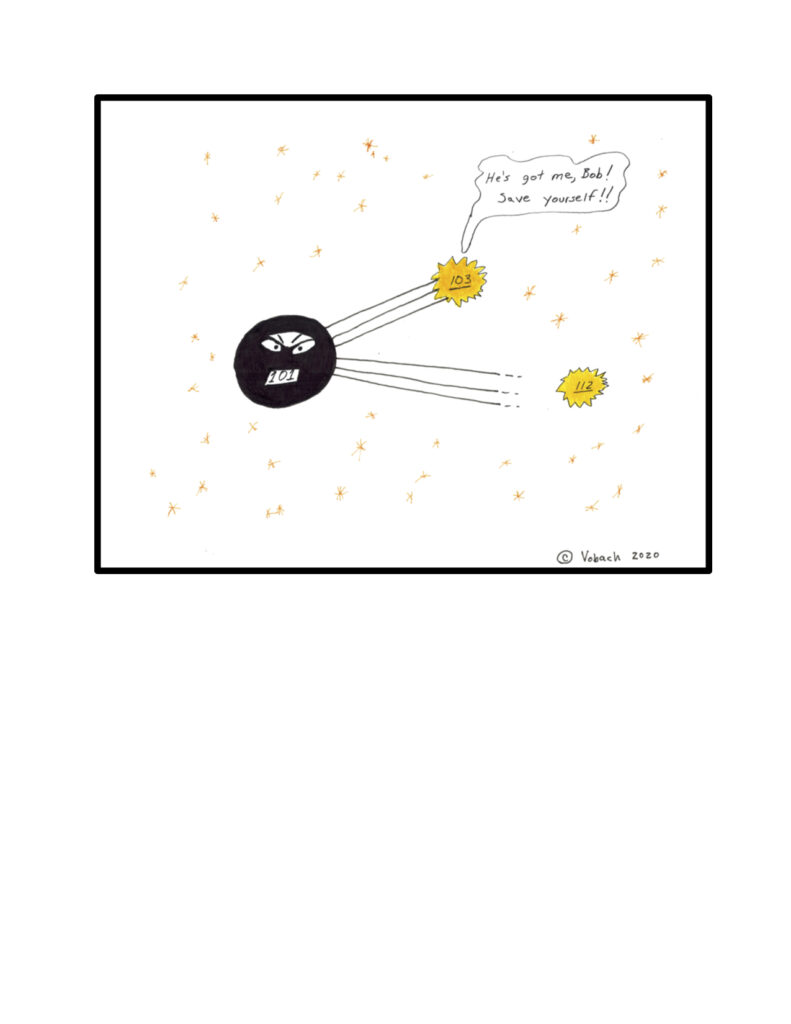

1. TiVo’s experience presents a particularly striking example of the abusive purposes for which the inter partes review regime can be employed. TiVo’s (and its subsidiaries’) patents have been the subject of well over one hundred inter partes review petitions since November 2016. Thirty-seven patents have been challenged—an average of 3.35 petitions per patent. In total, only about 5% of the challenged claims have survived. Many of these claims had been previously upheld against validity challenges by the International Trade Commission—a body made up of properly appointed principal officers.

In effect, inter partes reviews have allowed TiVo’s competitors to violate its patent rights and then, after having been adjudged guilty of that conduct in one adjudicatory forum (for example, the ITC), obtain a second bite at the apple via one or more inter partes review petitions. Even worse, after the first proceeding has exposed flaws in the infringer’s invalidity arguments, the infringer can use those proceedings as a roadmap to attempt to fix those flaws in the subsequent inter partes review. In effect, the first proceeding functions as a practice run for the infringer to test out its invalidity case and assess the weaknesses in it so it may avoid those weaknesses when it challenges the patent before the Board.

To take one illustrative example, Rovi, a TiVo subsidiary, asserted U.S. Patent Nos. 9,369,741 and 7,779,011 (among other patents) against Comcast Cable Communications in Certain Digital Video Receivers and Related Hardware and Software Components, Inv. No. 337-TA-1103 (U.S.I.T.C.). In the course of that proceeding, Comcast tried and failed to show that the claims of the ’741 patent were invalid in light of a prior-art reference called Sie. See Initial Determination on Violation of Section 337 and Recommended Determination on Remedy and Bond (Public) at 257–60 (June 27, 2019). Comcast also tried and failed to show that the claims of the ’011 patent were invalid as obvious over two prior-art references called Gross and Smith. See id. at 101–13. While the ITC investigation was ongoing, Comcast filed multiple inter partes reviews against the ’741 and ’011 patents. Using the Commission proceedings as a roadmap, Comcast ultimately succeeded in convincing the Board to invalidate those two patents based on the very same prior art that the ITC had already considered. Specifically, the PTAB concluded that the ’741 patent was obvious over Sie, see Comcast Cable Commc’ns, LLC v. Rovi Guides, Inc., No. IPR2019-00231, Paper 44 (P.T.A.B. May 8, 2020), and that the ’011 patent was obvious over Gross and Smith, see Comcast Cable Commc’ns, LLC v. Rovi Guides, Inc., No. IPR2019-00239, Paper 50 (P.T.A.B. June 30, 2020).3

This is not how the system is supposed to work. Patent owners should be entitled to some measure of repose. They should not be subjected to repeated attacks on the validity of their patents throughout their twenty-year term. The perpetual cloud of uncertainty that results from this system undermines the presumption of validity and harms incentives to innovate. It also flatly contradicts the original intent of the drafters of the AIA, who made clear that the new post-grant proceedings established by that statute were “not to be used as tools for harassment or a means to prevent market entry through repeated litigation and administrative attacks on the validity of a patent.” H.R. Rep. No. 112-98, pt. 1, at 48 (2011).

2. TiVo, unfortunately, is not an outlier with regard to its experience with the inter partes review system. According to TiVo’s research, for patents that have survived a validity challenge in district court or the ITC and are also challenged before the Board, the Board institutes inter partes review at a rate of 58% and cancels claims upon which review was instituted at a rate of 63%. These numbers are only marginally lower than the corresponding rates for all challenged patents, which are 66% and 75%, respectively. In other words, patents that have survived an expensive validity challenge in district court or the ITC are almost as likely to be reviewed—and ultimately invalidated—by the Board as a patent that was never the subject of litigation. It is little wonder that accused infringers use inter partes reviews to gain a second bite at the invalidity apple.

Amicus brief of TiVo Corporation at pages 6-9, footnotes omitted.