On the heels of his address to the IPO in Chicago this past week, Director Iancu will also be a featured speaker at the AIPLA annual meeting.

Mark Your Calendar

September 29th, 2018Quote of the day: GUST v. ALPHACAP

September 28th, 2018The quote of the day comes from today’s opinion in Gust v. Alphacap, __ F.3d __ (Fed. Cir. 2018)(slip op. at page 11):

Our case law recognizes that there is no bright line exclusion of software patents or business method patents from patent eligibility. Ultramercial, Inc. v. Hulu, LLC, 772 F.3d 709, 715 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (“[W]e do not purport to state that all claims in all software-based patents will necessarily be directed to an abstract idea.”); buySAFE, Inc. v. Google, Inc., 765 F.3d 1350, 1354 (Fed. Cir. 2014) (recognizing that Bilski v. Kappos, 561 U.S. 593, 611 (2010) did not create a general business method exception for patent eligibility).

Gust v. Alphacap, __ F.3d __ (Fed. Cir. 2018)(slip op. at page 11)(Judge Linn writing for the court).

Quiz of the day — name this case

September 24th, 2018Can you name the case for the quote that appears below:

In taking this step we are moved, to some extent, by the fact that the doctrine has been shown not to proceed from its purported well-springs. Even so, we would leave it undisturbed were it not the product of an essentially illogical distinction unwarranted by, and at odds with, the basic purposes of the patent system and productive of a range of undesirable results from the harshly inequitable to the silly.

Answer below the break

Revised procedure for docketing judgments and opinions

September 21st, 2018Marvin Gaye haunts Federal Circuit oral argument

September 20th, 2018Marvin Gaye made a special appearance at the Federal Circuit oral arguments a few months ago. During the oral argument of GLG FARMS LLC v. BRANDT AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS, LTD., No. 2017-1937 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 2, 2018), the audio equipment in the courtroom picked up an audio transmission from somewhere in the neighboring area. At one point in the oral argument, you can plainly hear Marvin Gaye’s “I heard it through the grapevine, not much longer would you be mine” playing in the background.

The court later granted a rehearing of the oral argument, because the interference was significant at certain points throughout the oral argument.

I hope the Federal Circuit’s ASCAP license is paid up.

Outer boundary of “reasonably pertinent”

September 17th, 2018The oral argument of the day is IN RE LIN, No. 2017-2263 (Fed. Cir. July 17, 2018). The oral argument was interesting in that the panel was searching for an outer boundary of what is pertinent art in the analogous art test.

In Wyers v. Master Lock, the court stated:

Two criteria are relevant in determining whether prior art is analogous: “(1) whether the art is from the same field of endeavor, regardless of the problem addressed, and (2) if the reference is not within the field of the inventor’s endeavor, whether the reference still is reasonably pertinent to the particular problem with which the inventor is involved.” Comaper Corp. v. Antec, Inc., 596 F.3d 1343, 1351 (Fed.Cir.2010) (quoting In re Clay, 966 F.2d 656, 658-59 (Fed.Cir.1992)).

Wyers v. Master Lock Co., 616 F.3d 1231 (Fed. Cir. 2010).

The court only issued a Rule 36 Judgment for In re Lin [Link]; but, you can listen to the oral argument here:

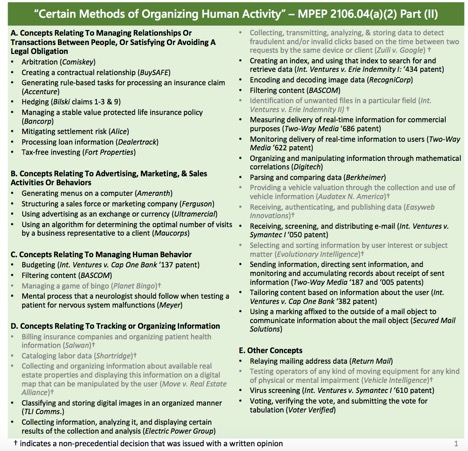

Certain Methods of Organizing Human Activity

September 15th, 2018Judge Taranto commented on what “organizing human behavior” means to him, in the oral argument of Interval Licensing v. AOL.

My impression was that his definition is much more limited than the broad categorical net that the USPTO has cast in its quick reference sheet:

I like how the USPTO has labeled this, however. Rather than saying that all methods of organizing human activity are abstract ideas, the USPTO has noted that only certain methods of organizing human activity have been found by the CAFC to meet step 1. In fact the USPTO has cautioned its examining corps with specific instructions not to generalize the “human activity” language:

II. “CERTAIN METHODS OF ORGANIZING HUMAN ACTIVITY”

The court have used the phrase “methods of organizing human activity” to describe concepts relating to interpersonal and intrapersonal activities, such as managing relationships or transactions between people, social activities, and human behavior; satisfying or avoiding a legal obligation; advertising, marketing, and sales activities or behaviors; and managing human mental activity. The term “certain” qualifies this category description as a reminder that (1) not all methods of organizing human activity are abstract ideas, and (2) this category description does not cover human operation of machines.

MPEP §2106.04(a)(2).

You can listen to the entire oral argument of Interval Licensing v. AOL here:

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Link].

A presumption of a technical advance

September 13th, 2018It seems to be more and more common for claims to pass muster under 35 USC §103 only to be shot down by the muddy metaphysics of 35 USC §101. I wonder if a panel of the Federal Circuit will someday pronounce a rule that if a claim satisfies 35 USC §103, then there is presumption that the claim is a technical advance. The burden would then be on the party challenging the claim to rebut that presumption.

For example, in Interval Licensing v. AOL, Judge Chen wrote for the court:

Considered as a whole, the claims fail under § 101’s abstract idea exception because they lack any arguable technical advance over conventional computer and network technology for performing the recited functions of acquiring and displaying information.

INTERVAL LICENSING LLC v. AOL, INC., No. 2016-2502 (Fed. Cir. July 20, 2018).

“Noah — get out of my office, you’re just an abstract idea”

September 12th, 2018There was a funny moment during the oral argument of Interval Licensing, LLC v. AOL, Inc. last December when Judge Plager explained why his law clerk was just an abstract idea:

“Why didn’t you walk it back”

September 7th, 2018In the recent decision of In re Facebook, the Federal Circuit reversed the Board’s rejection. One has a clear sense from listening to the oral argument that the PTO is not going to prevail — and it did not prevail. What is interesting to me is that Judge Moore asks the Solicitor’s Office during the oral argument why didn’t you “walk it back.”

The implication in the question is that the Solicitor’s Office somehow has authority to challenge the decision of the Board. That seems to be an unresolved issue — does the Solicitor’s Office of the PTO have the authority to challenge a Board decision of the PTO. If so, where is that authority spelled out? Personally, I think I would rather have the Federal Circuit have to deal with a few bad decisions by the Board, than frustrate the judicial independence of the Board by granting oversight authority to the Solicitor’s Office.

You can listen to the entire oral argument here:

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Link].

Welcome to CRAZYTOWN

September 4th, 2018Federal Circuit captions

August 29th, 2018It is curious that the Federal Circuit publishes the names of administrative judges in some appeal decisions but not in others. For example, in a recent appeal from the Board of Contract Appeals, the caption of the court’s decision in Truckla Services v. US Army Corps of Engineers recites:

Appeal from the Armed Services Board of Contract Appeals in Nos. 57564, 57752, Administrative Judge Elizabeth W. Newsom, Administrative Judge Mark N. Stempler, Administrative Judge Owen C. Wilson, Admin- istrative Judge Richard Shackleford.

However, in appeals from some other tribunals, the names of the administrative judges are not recited in the caption. This appears to be the case for ITC and PTAB appeals.

Quotes of the day

August 28th, 2018The first question, i.e., whether software may be a “component” of a patented invention under § 271(f), was answered in the affirmative in Eolas Techs. Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 399 F.3d 1325 (Fed.Cir.2005), which issued while the instant appeal was pending. In that case, we held that “[w]ithout question, software code alone qualifies as an invention eligible for patenting,” and that the “statutory language did not limit section 271(f) to patented `machines’ or patented `physical structures,'” such that software could very well be a “component” of a patented invention for the purposes of § 271(f). Id. at 1339.

AT & T CORP. v. Microsoft Corp., 414 F.3d 1366, 1369 (Fed. Cir. 2005)(Judge Lourie writing for the court), cert. granted 127 S.Ct. 467 (U.S. 2006) and judgment rev’d on other grounds, 127 S.Ct. 1746 (U.S. 2007).

Exact duplicates of the software code on the golden master disk are incorporated as an operating element of the ultimate device. This part of the software code is much more than a prototype, mold, or detailed set of instructions. This operating element in effect drives the “functional nucleus of the finished computer product.” Imagexpo, L.L.C. v. Microsoft, Corp., 299 F.Supp.2d 550, 553 (E.D.Va.2003). Without this aspect of the patented invention, the invention would not work at all and thus would not even qualify as new and “useful.” Thus, the software code on the golden master disk is not only a component, it is probably the key part of this patented invention. Therefore, the language of section 271(f) in the context of Title 35 shows that this part of the claimed computer product is a “component of a patented invention.”

Eolas Technologies Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 399 F.3d 1325, 1338-39 (Fed. Cir. 2005).

Section 271(f) refers to “components of a patented invention.” This statutory language uses the broad and inclusive term “patented invention.” Title 35, in the definitions section, defines “invention” to mean “invention or discovery” — again broad and inclusive terminology. 35 U.S.C. § 100(a) (2000). The next section in Title 35, section 101, explains that an invention 1339*1339 includes “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter.” 35 U.S.C. § 101 (2000). Without question, software code alone qualifies as an invention eligible for patenting under these categories, at least as processes. See In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526 (Fed.Cir.1994); AT&T Corp. v. Excel Communications, Inc., 172 F.3d 1352 (Fed.Cir.1999); MPEP § 2106.IV.B.1.a. (8th ed., rev. 2 2001). The patented invention in this case is such a software product. ‘906 patent, col. 17, ll. 58 — col. 18, ll. 30. Thus, this software code claimed in conjunction with a physical structure, such as a disk, fits within at least those two categories of subject matter within the broad statutory label of “patented invention.”

Eolas Technologies Inc. v. Microsoft Corp., 399 F.3d 1325, 1338-39 (Fed. Cir. 2005).

Color coded briefs to explain a claim’s evolution

August 26th, 2018During the oral argument of PERSONALIZED MEDIA COMMUNICATIONS, LLC v. Amazon. com, Inc., No. 2017-1441 (Fed. Cir. Mar. 13, 2018), the Federal Circuit seemed rather receptive of Amazon’s color coded brief reflecting the evolution of a claim during prosecution.

You can see the brief [here].

Judicial Canons

August 23rd, 2018I was wondering to myself how panel stacking and panel manipulation would be viewed under the canons of judicial ethics. The uscourts.gov site has a good link to the Code of Conduct for US Judges. It is available [here].

At the top of the list is Canon 1; it emphasizes preserving the independence of the judiciary:

Canon 1: A Judge Should Uphold the Integrity and Independence of the Judiciary

An independent and honorable judiciary is indispensable to justice in our society. A judge should maintain and enforce high standards of conduct and should personally observe those standards, so that the integrity and independence of the judiciary may be preserved. The provisions of this Code should be construed and applied to further that objective.

COMMENTARY

Deference to the judgments and rulings of courts depends on public confidence in the integrity and independence of judges. The integrity and independence of judges depend in turn on their acting without fear or favor. Although judges should be independent, they must comply with the law and should comply with this Code. Adherence to this responsibility helps to maintain public confidence in the impartiality of the judiciary. Conversely, violation of this Code diminishes public confidence in the judiciary and injures our system of government under law.

The Canons are rules of reason. They should be applied consistently with constitutional requirements, statutes, other court rules and decisional law, and in the context of all relevant circumstances. The Code is to be construed so it does not impinge on the essential independence of judges in making judicial decisions.

The Code is designed to provide guidance to judges and nominees for judicial office. It may also provide standards of conduct for application in proceedings under the Judicial Councils Reform and Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980 (28 U.S.C. §§ 332(d)(1), 351-364). Not every violation of the Code should lead to disciplinary action. Whether disciplinary action is appropriate, and the degree of discipline, should be determined through a reasonable application of the text and should depend on such factors as the seriousness of the improper activity, the intent of the judge, whether there is a pattern of improper activity, and the effect of the improper activity on others or on the judicial system. Many of the restrictions in the Code are necessarily cast in general terms, and judges may reasonably differ in their interpretation. Furthermore, the Code is not designed or intended as a basis for civil liability or criminal prosecution. Finally, the Code is not intended to be used for tactical advantage.