Microsoft has now filed its request for a rehearing en banc in the I4I v. Microsoft appeal: [Read].

Microsoft Requests Rehearing En Banc in I4I case

January 9th, 2010What does “connect” mean?

January 6th, 2010If you have ever written mechanical patents or spent time analyzing them, you have probably run across the issue of how broadly should the word “connect” be interpreted. (Similarly, you have probably contemplated the meaning of “coupled with.”) The case of Restaurant Technologies, Inc. v. Jersey Shore Chicken, 2009-1176, (Fed. Cir. January 6, 2010) broached this issue with respect to the word “interconnecting.” The patent at issue concerned a chicken fryer.*

The claim term at issue read:

(e) piping network interconnecting said first and second containers, said filter unit and said first and second couplings.

One of the interesting aspects of the oral argument was when Peter Lancaster of Dorsey and Whitney’s Minneapolis office made the argument that the defendant’s own patent (stipulated to describe the accused device) described the elements of the allegedly infringing product as “connected.” [Listen]. In my review of the court’s opinion, I did not see that the panel ever addressed that argument.

The panel also noted that the doctrine of equivalents would not cover indirectly connected elements — elements are either connected or not connected.

Furthermore, the court was correct in limiting possible equivalents as a matter of law, finding that claim 8, paragraph (e), “warrant[s] few or no equivalents because there are no insubstantial or trivial changes that could be made to this limitation; the specified components are either connected or not connected to one another by a piping network.” Summary Judgment Opinion, 2007 WL 4081737 at *19. Based on the claim construction, the court was correct in finding that Oilmatic was entitled to summary judgment of noninfringement.

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Read].

*Appropriately, the inventors for the chicken fryer patent at issue hail from Kentucky.

Do you speak American?

January 3rd, 2010PBS has an interesting website on American English at http://www.pbs.org/speak/ that they title “Do you speak American?” One fun page at the site is an interactive quiz to see if you can match a speaker to a region of the country: [Link].

Another page explains how various presidents have coined new words throughout the years, such as “administration,” “lunatic fringe,” and “misunderestimate”: [Link].

The article refers to one who coins new words as a neologist. My reaction to reading that was “Oh, they meant to say lexicographer.” But, it turns out that PBS has the better word. According to my dictionary, a lexicographer is “a writer, editor, or compiler of a dictionary.” However, neologize means “to make or use new words or create new meanings for existing words.” It would seem that a lexicographer is merely a person who records established definitions rather than the more creative neologist who coins entirely original meanings for words.

A lesser known corollary to the lexicographer [sic: neologist] rule is that a patentee is also entitled to be his or her own grammarian. See Chicago Steel Foundry Co. v. Burnside Steel Foundry Co., 132 F.2d 812, 814-15 (7th Cir. 1943), cited in Jonsson v. Stanley Works, 903 F.2d 812, 820-21 (Fed. Cir. 1990).

*By the way, while playing SCRABBLE over the holidays, I tried to explain to my family that as a patent attorney, I was entitled to be my own lexicographer [sic: neologist] when proposing new words on the board. They didn’t buy it.

Lodestar Analysis: “Did you have a party?”

December 30th, 2009One of the nice personality traits of the judges of the Federal Circuit is that they have healthy senses of humor. Judge Plager’s rather wry sense of humor demonstrated itself in two recent oral arguments.

In the oral argument for IN RE ELECTRO-MECHANICAL INDUSTRIES, 2008-1530, (Fed. Cir. Dec. 22, 2009), the court was trying to determine why the district court judge had increased the award of attorneys’ fees in a bankruptcy estimation proceeding. Judges Moore and Plager were intently discussing with plaintiff’s counsel the Lodestar analysis for contingency cases and inquiring about his reaction at the time that the district court judge significantly enhanced the attorneys’ fee award. As you’ll hear, Judge Plager then asked “I bet you had a party, didn’t you?” [Listen]. For the record, I’m pretty sure that whether one had a party is not the current standard of review of a Lodestar analysis.

In the oral argument of another recent case, In re Medicis Pharmaceutical Corporation, 2009-1291, (Fed. Cir. Dec. 14, 2009), the Associate Solictor for the PTO made a conscientious effort during oral argument to correct a statement that was in his brief. Judge Plager’s tongue-in-cheek remark was “Which raises the question ‘Were you lying then, or are you lying now?’ ” [Listen].

How many references are too many?

December 28th, 2009The Federal Circuit recently decided In re Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp., 2009-1291, (Fed. Cir. December 14, 2009), an appeal from the Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences. An interesting issue that arose during oral argument was how many references may the PTO reasonably combine in making a 103 rejection.

Many patent attorneys have been frustrated at one time or another by an examiner seemingly hell-bent on rejecting a claim by combining an endless number of references so that all the elements of the claim could be accounted for in a 103 rejection. Therefore, it was interesting to hear this exchange between Judge Rader and the Associate Solicitor for the PTO during the oral argument of In re Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp. as to how many references are too many: [Listen]. Judge Rader commented that when you start combining three references together rather than two, that suggests the person of ordinary skill has to have an awful lot of understanding.

Those who have researched this issue in the past are probably familiar with the MPEP section 2145, V. which states:

Reliance on a large number of references in a rejection does not, without more, weigh against the obviousness of the claimed invention. In re Gorman, 933 F.2d 982, 18 USPQ2d 1885 (Fed. Cir. 1991) (Court affirmed a rejection of a detailed claim to a candy sucker shaped like a thumb on a stick based on thirteen prior art references.).

In light of the Supreme Court’s decision in KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex, Inc., 550 U.S. 398 (2007), perhaps it would be clarifying for the Federal Circuit to consider Judge Rader’s position in a forthcoming opinion.

At another point during the oral argument, Judge Rader commented about long-felt need. The patent (which was on appeal from the Board after a reexamination) concerned a facial cleansing product. And, Judge Rader noted that since the need for a good facial cleansing product has probably been in existence since the origin of mankind, that shouldn’t that be a significant factor to consider in the obviousness analysis: [Listen].

The panel issued a Rule 36 affirmance of the Board decision.

Logan, Jr. v. Hormel Foods

December 24th, 2009In the spirit of the holidays, I thought it might be fun to revisit a 2007 decision that involved spiral sliced ham. The claim at issue in this case read:

A boneless sliced meat having its meat arranged in the form of a continuous spiral cut about an axis of the meat, the axis being created by temporary insertion of a support member in the meat, wherein the depth of said cut is limited to leave an uncut core of meat, said core being of sufficient cross-section to cause the boneless sliced meat to retain its shape when the support member is removed.

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Read].

Repeated Use of Permissive Language

December 22nd, 2009One of the reasons that I enjoy listening to the recordings of the Federal Circuit oral arguments is for the creative arguments that are not eventually addressed in the court’s opinion. Oftentimes, there is no need for the court to address these arguments in the resulting opinion because another issue on appeal makes the arguments moot. Such was the case in Intellectual Science and Technology v. Sony Electronics, Inc., 2009-1142, (Fed. Cir. Dec. 15, 2009).

One of the issues that was on appeal in Intellectual Science and Technology v. Sony Electronics, Inc. was whether repeated use of the phrase “multitasking” in describing an embodiment in a permissive context (e.g., “capable of multitasking”, “including multitasking”, “such as multitasking”) mandated that the “multitasking” language in the preamble be considered as an element in the claim. This is the query Judge Rader had for plaintiff-appellant’s counsel: [Listen]. And, this is the exchange between Judge Rader and defendant-appellee’s counsel on the same issue: [Listen].

The court did not have to address the issue in the opinion. Instead, it said:

Intellectual Science also appeals the district court’s construction of the term “with multitasking function” in the preamble of claim 1 of the ’575 patent. The construction of that term, however, does not affect the issue of adequate information to create a factual issue on infringement of the “data transmitting means” in the accused devices. Because Intellectual Science did not show a genuine issue of material fact on one of the limitations in the accused devices, this court need not reach the district court’s construction of another. See TechSearch, 286 F.3d at 1371 (“To establish literal infringement, all elements of the claim, as correctly construed, must be present in the accused system.”).

Judge Rader also noted in one of his hypotheticals that he is an ABBA and a Beatles fan. Counsel quickly invoked the title of the song “Dancing Queen” by ABBA into his response — proving, as many have long suspected, that the rough and tumble world of patent litigation eventually turns all patent litigators into ABBA fans [Listen].

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

No new issues during rebuttal argument

December 17th, 2009As you may recall, an oral argument at the Federal Circuit is typically divided into fifteen minutes per side. The appellant argues first and is entitled to reserve some of his or her fifteen minutes for rebuttal argument. Oftentimes, the appellant runs into his or her rebuttal time during the initial argument. This can occur, for example, when there is extensive questioning from the court or poor clock management by the appellant.

The presiding judges of the panels at the Federal Circuit are pretty accommodating when it comes to the formalities of oral argument. They often allow a party to run long and then restore the full rebuttal time. They seem more inclined to do this if the reserved rebuttal time is five minutes or less. In such instances, the appellee is given an equal extension so that both sides have an equal amount of argument time.

It’s been my impression that Judges Mayer and Newman run the tightest ships when it comes to oral argument. While they will often give an appellant his or her full requested rebuttal time when time runs over, that is not always the case. They are also more likely to instruct an appellant to wrap up and surrender the podium when the appellant encroaches on his or her rebuttal time during the main argument.

One formality that is strictly enforced by the Federal Circuit is the rule that the appellant should not raise new issues on rebuttal because the appellee does not have a chance to respond to them. The presiding judges are uniform in enforcing this rule. Thus, an appellant needs to be careful to argue all issues that he or she wants to address in the oral argument during the main argument. This may require letting the presiding judge know that there is an additional issue to be mentioned prior to concluding the main argument. As an example of the trap that can befall an appellant, Judge Mayer recently instructed an appellant to wrap up at about the twelve minute mark of oral argument [Listen] and then did not allow the appellant to argue new issues during rebuttal [Listen].

Judge Moore Recuses Herself

December 14th, 2009Judge Moore recused herself last Thursday from the case Technical Furniture Group, LLC v. CBT Supply, Inc. Chief Judge Michel took her place on the panel. Chief Judge Michel explained that a computer performs the random selection of a replacement judge when a judge recuses herself — and he was the random selection in this instance. You can listen to the explanation here: [Listen].

More on “common sense”

December 13th, 2009The panel in Source Search Technologies, LLC v. LendingTree, LLC weighed in on the common sense issue during oral argument. You can listen to Judge Plager’s remarks and Judge Rader’s tongue in cheek remarks here: [Listen].

The invention at issue in this case was invented in the 1995-96 timeframe. At one point during the oral argument Judge Rader made the interesting inquiry of appellee’s counsel that given the nascent stage of the internet in 1995-96, what would have been the motivation or market force to combine brick and mortar references to achieve the claimed invention. [Listen].

Judge Plager had the following follow-up comment for appellee’s counsel [Listen] to which Judge Rader responded.

Query: People often note the speed with which the internet has evolved. Should that change the calculus in the consideration of “long-felt need” under the Graham factors? If it takes less time for innovation to occur in the art of computers and the internet as opposed to the art of plows and combines, wouldn’t it be appropriate for long-felt need to be assessed relative to the speed with which an industry evolves?

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Read].

You can listen to the entire oral argument here: [Listen].

Common sense

December 11th, 2009There are a variety of views on what constitutes common sense. Here are a few notable quotations:

“Le sens commun n’est pas si commun.” –Voltaire

“Common sense is very uncommon.” — Horace Greeley

“Common sense ain’t so common.” — Will Rogers

“Common sense is the collection of prejudices acquired by age eighteen.” – Albert Einstein

“Common sense is what tells us the Earth is flat and the Sun goes around it.” — Anonymous

“The philosophy of one century is the common sense of the next.” – Henry Ward Beecher

“Science is nothing, but trained and organized common sense.” – Thomas H. Huxley

“Common sense is genius dressed in its working clothes.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Common sense is the genius of humanity.” – Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe

“The last time anybody made a list of the top hundred character attributes of New Yorkers, common sense snuck in at number 79.” – Douglas Adams

“Common sense is only a modification of talent. Genius is an exaltation of it. The difference is, therefore, in degree, not nature.” — Edward G. Bulwer-Lytton

“Common sense –Sound practical judgment; that degree of intelligence and reason, as exercised upon the relations of persons and things and the ordinary affairs of life, which is possessed by the generality of mankind, and which would suffice to direct the conduct and actions of the individual in a manner to agree with the behavior of ordinary persons.” — Black’s Law Dictionary

———————————————————————————————-

The Federal Circuit had an opportunity to expand upon the “common sense” issue recently in Perfect Web Technologies, Inc. v. INFOUSA, Inc. One of the issues the Federal Circuit panel (Judges Linn, Dyk, and Prost) confronted was how does one determine common sense. And, since this case was before the court on review of a summary judgment decision, is common sense a factual issue that, if disputed, is weighed in favor of the non-moving party?

The Federal Circuit looked to the parties to try to understand how common sense in the context of an obviousness determination under KSR v. Teleflex should be applied. Here are a couple of interesting sound bites from that discussion: [Listen] and [Listen].

This oral argument also discussed the “tied to a machine” aspect of the Bilski test. It was not necessary to address the 101 issues in the court’s opinion, however, because the court affirmed the district court on the obviousness issues.

You can read the court’s opinion here: [Read].

You can download the entire oral argument here: [Listen/Download].

Hewlett Packard Co. v. Acceleron LLC

December 8th, 2009All patent owners are equal under the law. After the Hewlett Packard Co. v. Acceleron LLC decision, however, some are more equal than others. In Hewlett Packard Co. v. Acceleron LLC, the Federal Circuit took note of the fact that the patent owner was “solely a licensing entity” in assessing whether HP was entitled to bring a declaratory judgment action. When a patent owner is a patent holding company, one is now entitled to consider that as a relevant factor in assessing whether a court has declaratory judgment jurisdiction.

One might think that the panel that decided the case frowned upon patent holding companies. However, according to these remarks by Chief Judge Michel during the oral argument, such is not the case: [Listen].

Chief Judge Michel seemed frustrated by the vague language used by the US Supreme Court in its Medimmune v. Genentech, 549 US 118 (2007) decision for evaluating when it is proper for a party to bring a declaratory judgment action: [Listen].

This case now begs the question of what constitutes “solely a licensing entity.” Is an independent inventor who doesn’t practice his or her patent solely a licensing entity? Is it sufficient if he or she simply doesn’t practice one claim of the patent, since each patent claim in theory stands on its own? Is a research institution a patent holding company? Is the US government a patent troll? Is IBM, the leader in obtaining US patents, solely a licensing entity with respect to its patents that it doesn’t implement? And, perhaps most importantly, will this special recognition of entities that are soley focused on licensing their patents, make it easier or more difficult for them to obtain injunctions for patent infringement?

It will be interesting to see in the next few months if there is a surge in filings of declaratory judgment actions based on this case and past correspondence by patent owners.

You can read the court’s decision here: [Read].

Judge Daniel M. Friedman

December 5th, 2009The answer to the quiz in the previous post is: Judge Daniel M. Friedman.

At age 93, Judge Friedman still regularly takes part in Federal Circuit cases. Almost his entire adult life has been in public service:

Born 1916 in New York City, NY

Education:

Columbia University, A.B., 1937

Columbia Law School, LL.B., 1940

Professional Career:

Private practice, New York City, 1940-1942

Attorney, Securities and Exchange Commission, Philadelphia, PA, and Washington, DC, 1942

U.S. Army, 1942-1946

Attorney, Securities and Exchange Commission, Philadelphia, PA , and Washington, DC, 1946-1951

Assistant chief, Appellate Section, Antitrust Divison, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC, 1951-1959

Office of the U.S. Solicitor General, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC, 1959-1978

Assistant to the U.S. solicitor general, 1959-1962

Second assistant to the U.S. solicitor general, 1962-1968

First deputy U.S. solicitor general, 1968-1978

Acting U.S. Solicitor General, 1977

Federal Judicial Service:

Judge, U. S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

Reassigned October 1, 1982; Assumed senior status on November 1, 1989.

Chief judge, U.S. Court of Claims, 1978-1982.

The biographies of the other judges of the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit can be found [Here] and [Here].

For some reason, the biographies of only two former judges (Judge Howard T. Markey and Judge Wilson Cowen) are included on the Federal Circuit web site.

Public Service

December 1st, 2009“I have the consolation of having added nothing to my private fortune during my public service, and of retiring with hands clean as they are empty.”

–Thomas Jefferson

I am always struck by the impressive careers in public service by many of our judges. Unfortunately, as Chief Judge Michel noted in his retirement announcement the other day, the judges of the Federal Circuit have served while apparently not receiving a pay raise in the last twenty years.

One notable example of a distinguished career in public service is the Federal Circuit judge featured on the following recording. It is an oral argument from the 1970’s before the US Supreme Court. Can you name him? [Listen] Hint: Prior to being appointed to the bench, he was the acting Solicitor General of the United States.

Deja vu all over again

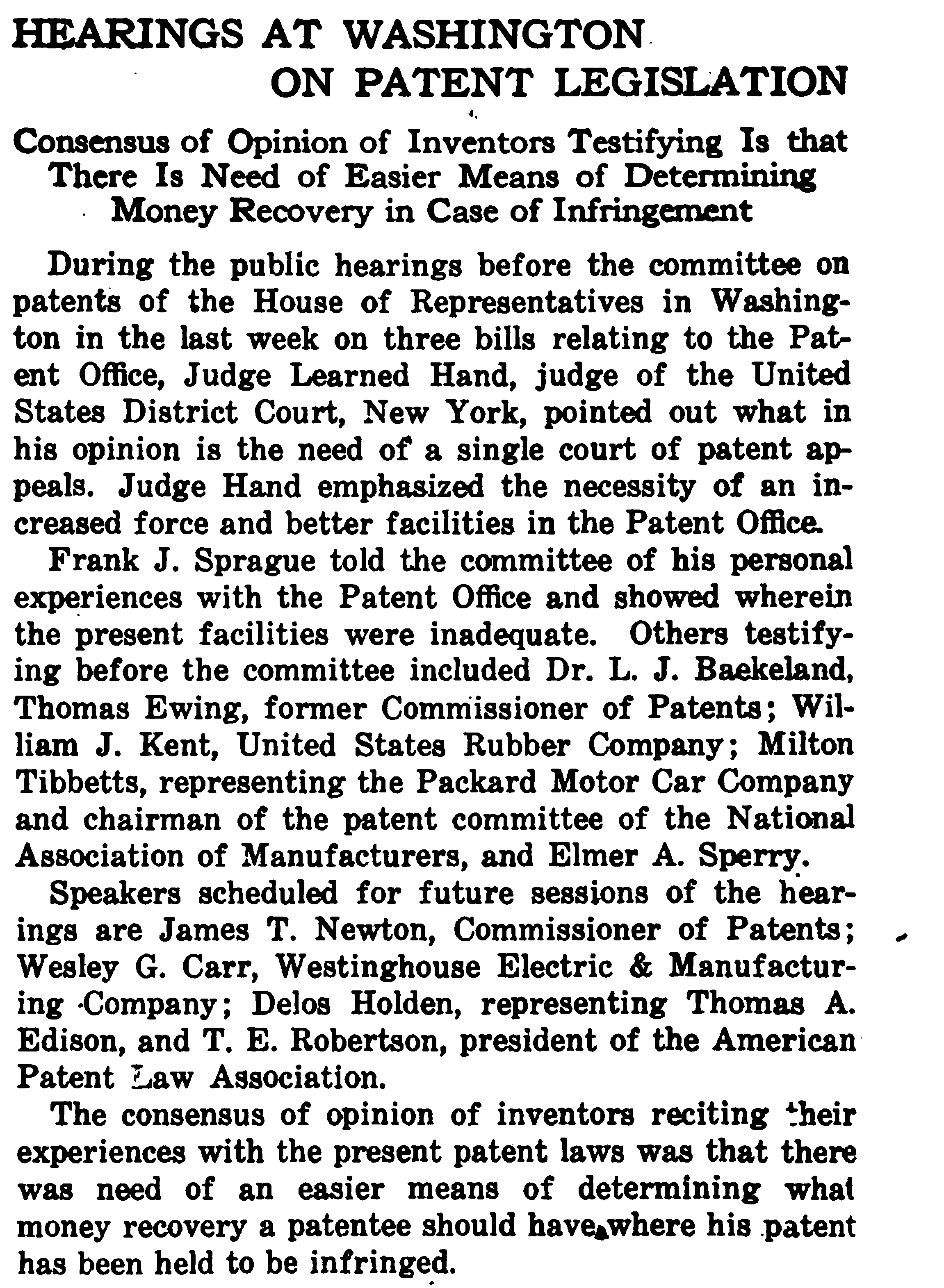

November 30th, 2009I stumbled across this excerpt from the July 19, 1919 edition of the magazine Electrical World the other day.

Note that ninety years later we still have a call for damages reform, more examiners, and an improved patent office. I suspect Learned Hand would at least have been pleased to see the establishment of the Federal Circuit.