I find it pretty tough to read too much out of the oral argument in i4i v. Microsoft. It was strange that Judge Schall did not ask many questions during the oral argument — which might be an indicator of his positions on the issues. And, I found it strange that the panel did not have many questions for i4i’s counsel about the claim construction issues raised by Microsoft’s counsel. Instead, the panel seemed to focus more on the damages issues when questioning i4i’s counsel.

What really piqued my interest is an issue that isn’t on appeal. Namely, I’m curious how the Federal Circuit’s recent line of cases on “full scope of enablement” would affect the validity of the 5,787,449 patent. Figures 7 and 9 from the ‘449 patent are shown below. Counsel for i4i referred to these figures during oral argument by stating:

The fact is that Your Honors have focused correctly on Figure 9. You can also focus on Figure 7, which also shows that the user has access at the same time to both the mapped content and the metacode map. And you can also look at the very top, oval 132, input device for creating content and selecting metacodes. The user has access to both, and it’s not only the Figure 9 statement that has the statement about updating. But, if you look at column 6, lines 14 and 15, the mapped content area and metacode map is updated as changes are made.

Fig. 7

Fig. 9

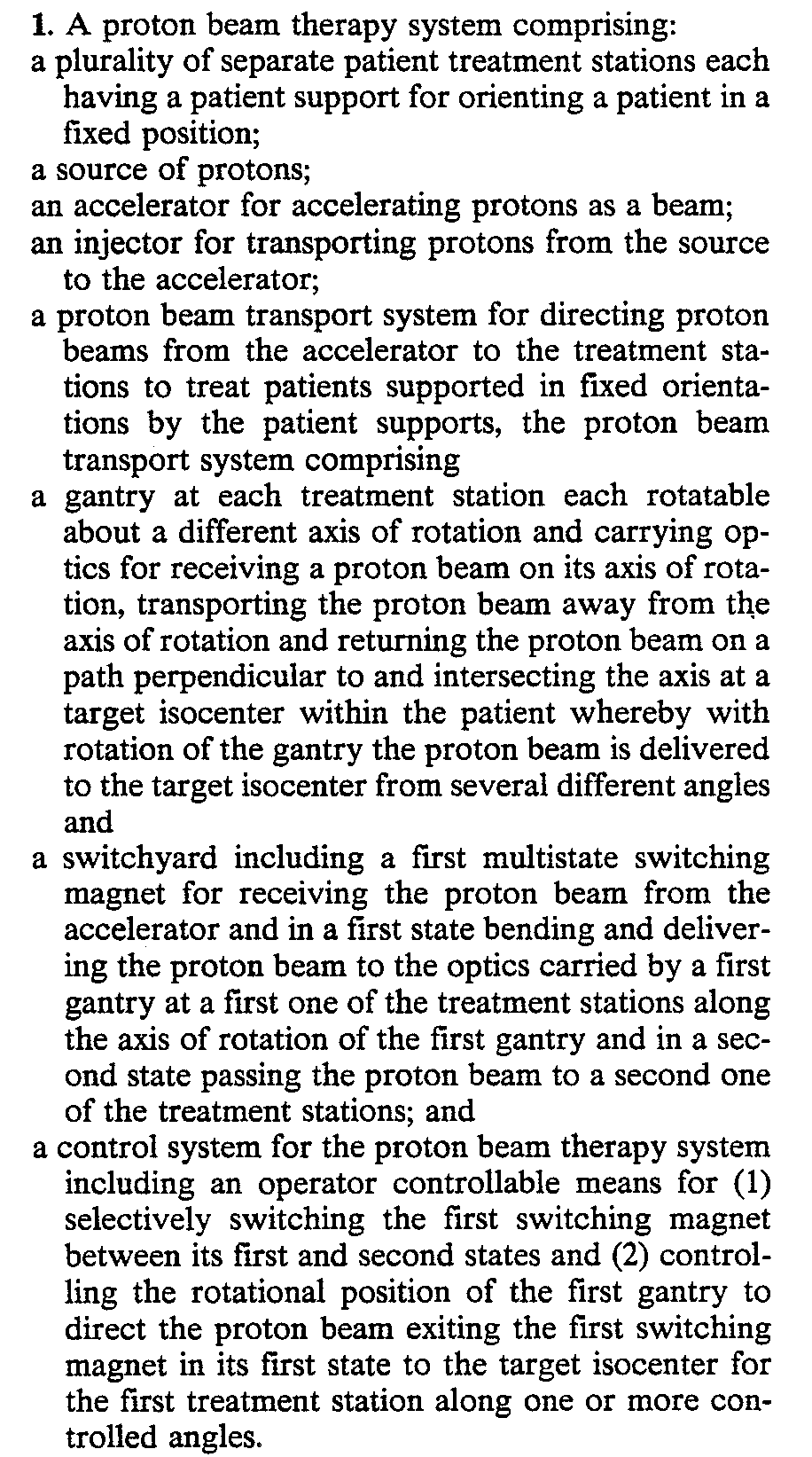

The ‘449 patent has an independent system claim and an independent method claim. Only the method claim was asserted. These system and method claims are shown below:

As you can see, figures 7 and 9 utilize blocks with the “means for” language contained in the blocks. There appears to be no structure identified in the figures for at least some of the “means for” blocks. Furthermore, the detailed description linked to these blocks appears to describe these blocks with the same “means for” language used inside the blocks (e.g., col. 14, lines 26-28 “compiles the selected metacodes using the means for selecting, locating, and addressing metacodes represented in Box 144”). Hence, one might argue that not all of the “means” elements in the claims are linked to any structure in the specification or drawings and thus would fail to meet the requirements of section 112, paragraph 6. See Default Proof Credit Card Systems, Inc. v. Home Depot U.S.A., Inc., 412 F.3d 1291 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (“A structure disclosed in the specification qualifies as ‘corresponding’ structure only if the specification or prosecution history clearly links or associates that structure to the function recited in the claim . . . . This duty to link or associate structure to function is the quid pro quo for the convenience of employing section 112, paragraph 6”).

In Automotive Technologies International, Inc. v. BMW of North America, Inc., 501 F.3d 1274 (Fed. Cir. 2007), the Federal Circuit applied a full scope of enablement theory. The court noted that the mere boxed figure of an electronic sensor and a few lines of description fail to apprise one of ordinary skill how to make and use an electronic sensor.

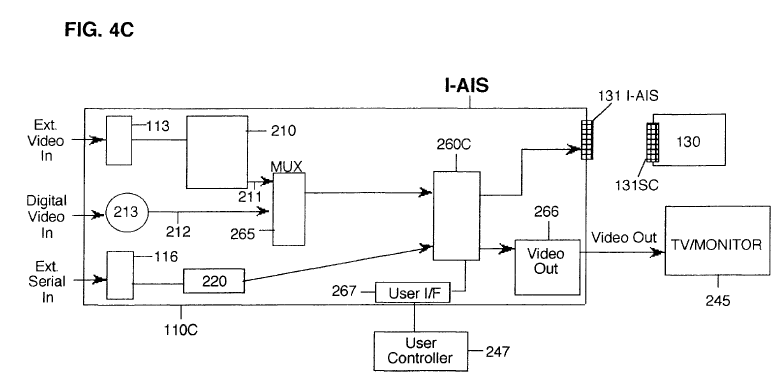

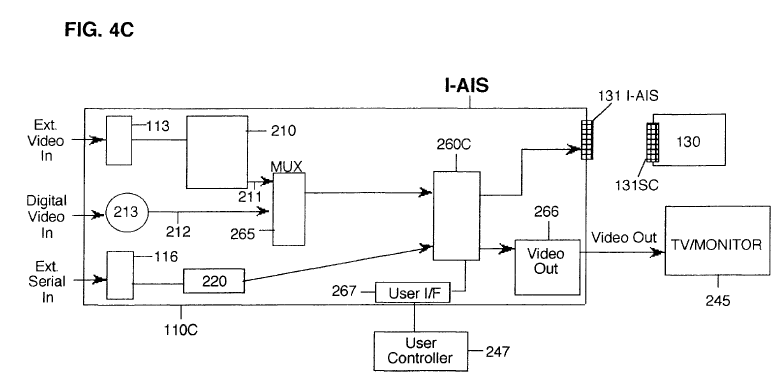

Thus, a means plus function limitation that was construed to include both mechanical and electrical sensors was deemed not to be enabled to the “full scope of enablement” even though the mechanical sensor was sufficiently enabled. And, in Sitrick v. Dreamworks, 516 F.3d 993 (Fed. Cir. 2008), the Federal Circuit found that a controller represented by a blank box 260C

was not sufficiently enabled to perform the steps of “selecting” and “analyzing” a predefined character image in a movie or “integrating” or “substituting” an image in movies.

Taken to its extreme, one wonders whether under the “full scope of enablement” theory an insufficiently enabled means plus function element would necessarily require that a corresponding step (or act) in a method claim be deemed insufficiently enabled. Thus, for example, if the claim element “means for compiling said metacodes of the menu by locating, detecting and addressing the metacodes in the document to constitute the map and storing the map in the metacode storage means” in claim 1 had been found to be insufficiently enabled, would it necessarily mandate that the corresponding claim element “compiling a map of the metacodes in the distinct storage means, by locating, detecting and addressing the metacodes” in claim 14 was insufficiently enabled.